List of works

2023

Quartet Black

for string quartet

Grey and Green are all my Light

a song-cycle for medium voice and piano - texts by Robert Jellicoe

2021

Crystal

for piano quartet

2020

Homecoming

for two violins

2019

The Little That Was Once a Man

song-cycle for high voice and piano - texts by Bryan Heiser

2018

Cello Sonata

for cello and piano

2017

Machine Dream

a short opera for singers aged 7-11 accompanied by professional musicians

2015

Instinctive Ritual

for four hands at one piano

2014

Variations on a Theme of Cole Porter

for piano

2013

Trans-Atlantic Flight of Fancy

for NOW Ensemble (flute, clarinet, electric guitar, piano, double bass)

2012

Intermezzo

for piano

2006

The Ascent of F6

Incidental music and songs for the play by Auden/Isherwood, including a 'concert' version

Publishing

People often ask me about the mechanics of producing a musical score. Do I still write with a pencil and paper? Do I have a publisher? How do you produce musical graphics? So here is some information about how music, in a notated form, is actually produced and distributed.

I am self-published, and although I engage a professional printer and binder to produce the actual scores, I typeset music myself using desktop software called Sibelius. (There are various musical notation software programmes – for a more detailed discussion on the merits of Sibelius, less well-known programmes like Lilypond, or the more recent Dorico, hang around a student bar near a college or university music department following a new music workshop. Discussions can get quite heated…!)

I typeset my music only having written a great deal of it down with pencil and paper – but that is a very personal thing. I suppose I am quite old-fashioned in this, but then again writing down music is pretty old-fashioned anyway – certainly in the global musical context of the 2020s, when most creators would consider a ‘piece’ to be an audio track rather than a piece of paper. But zoom out a bit further in time and writing down music can be seen as a very modern thing to do, only really being widespread in the last few hundred years, and then only in the Western musical tradition, with music-making of all kinds and in many other cultures having flourished with very limited recourse to notation for thousands of years prior. Its quite likely that our current emphasis on the aural, rather than printed, sharing of music is just a return to common practice, and gradually we shall look back on the period of c.1700 to 2000 as a bit of a historical anomaly when composers actually wrote things down.

Anyway, the point is I have to write music by hand, on paper – not just because I am used to it, but because the use of a static physical space (a blank piece of paper) is central to my creative process. When one writes music on paper there is a sense of manipulating physical shape and space, rather than sound. This sense is heightened by the physical touch of a pencil – although I never rub anything out, and when I put a line through notes the aim is not to delete them permanently but rather indicate that I believe it does not work at this particular juncture or in reference to the particular issue at hand.

Composers nearly always use the word ‘sketch’ when referring to the early drafts of a composition, which is an interesting word to use as it is much more commonly associated with visual art. But that is absolutely how I ‘sketch’ music – visually, spatially, using the paper more as a canvas than a linear module. The process is certainly much less to do with sounds and notes than it is to do with time and shape. Actually that is a massive understatement – when I sketch I almost never think about notes at all – its all gestures, shapes, and making connections. I’m going to end up manifesting that through notes, but the decision of which notes those should be is almost never uppermost in mind during those initial deliberations.

So why can I not do this on a computer programme, like I am typing this straight onto a keyboard? Well, if you are writing text, you can write ‘A’ with a pencil, or you can type ‘A’ on a keyboard, and either way the shape ‘A’ will appear on your respective media. But the process of doing that in notes is not, for me, composing music, but rather transcribing it – and while no doubt there were many composers (Mozart the most infamous) who wrote down music already conceived in their heads, I don’t write my music like that. So as I play around with shapes and ideas, the physical action of going up and down on the stave, feeling the contour of the notes go up and down, the effort and tension of moving from one pitch to another – these are all engendered in the act of writing the pitches with your hand, whether in pitch (up and down) or in time (left and right).

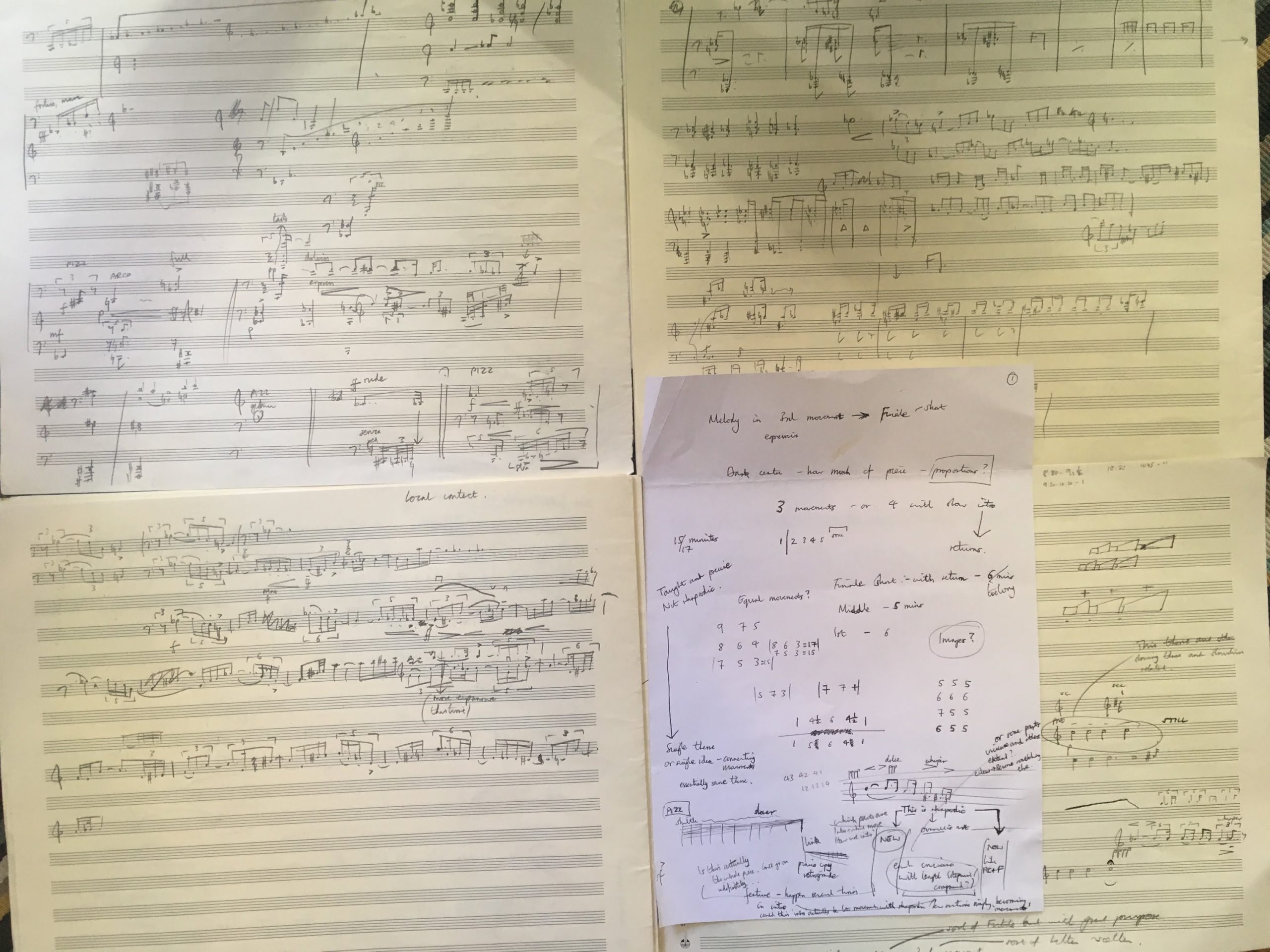

My sketches range in format from A3 or occasionally larger sheets of paper to a notebook or musical memoranda on backs of envelopes. I have become deft at whooshing five parallel lines on any blank piece of paper which falls to hand. I veer between trying to keep my sketches systemised, collated and dated, like a sort of diary, to wallowing in more of a melting-pot of ideas. Either way, after a certain period of time – it can be days, months, even years – I end up with a huge number of pieces of paper which look something like this:

There is little here which could be defined as a piece, or even a section, or even (quite often) a sound. I often write words – about what I want the piece to be, or not be. But it is with these materials that I can begin to discover what the piece is, as an object in itself, a series of events and not just a jumble of ideas or intentions.

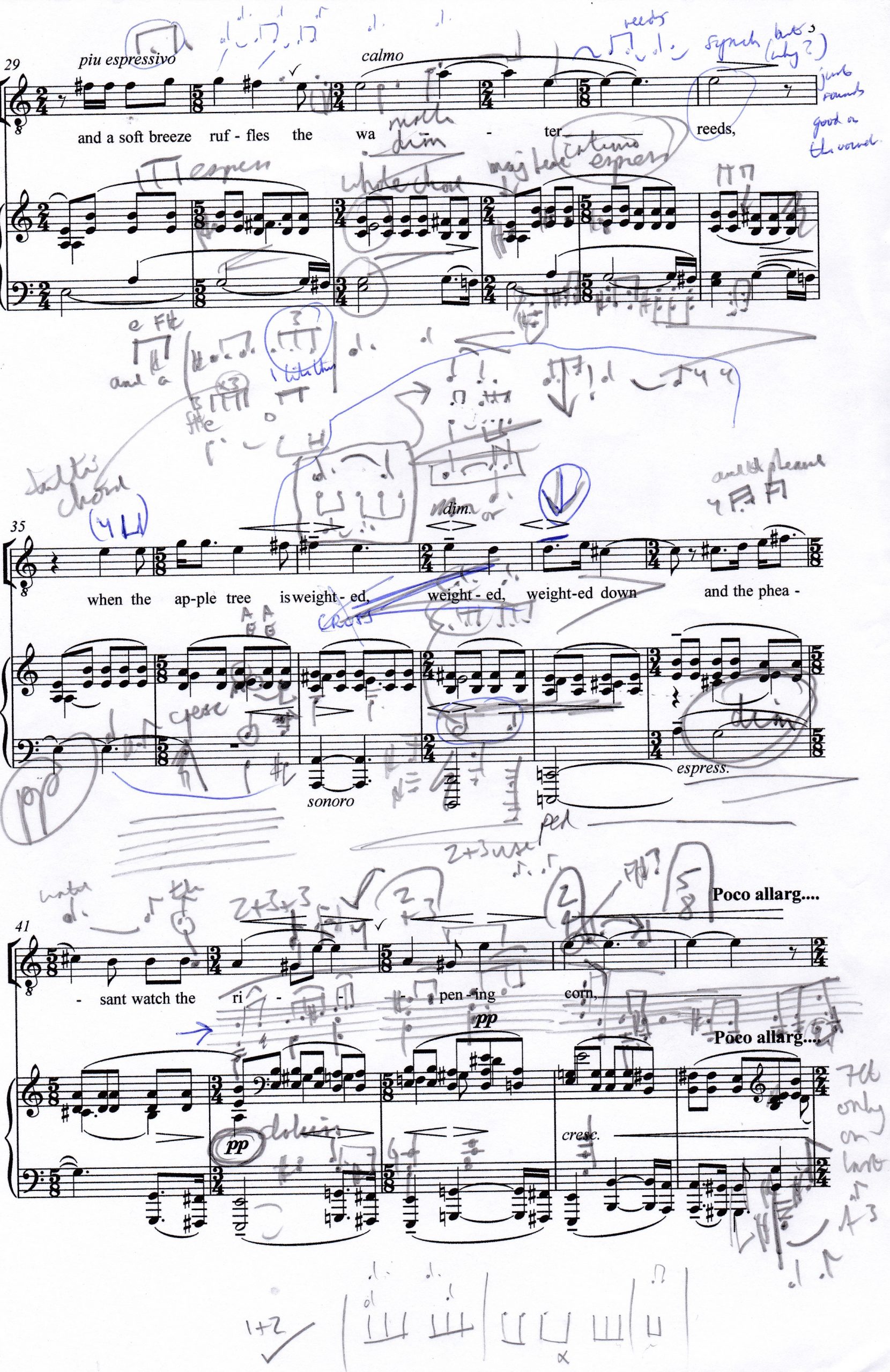

What I do not do at this stage, which I perhaps would have done a few years ago, was to try and make a ‘fair copy’ by hand. I now start putting it straight onto the computer, and then go back and forth between moulding it on screen and making additions on paper. At some point there is a sort of framework to the piece – although that can of course change, and usually does – but at some point I can print off a more or less complete framework of the piece, however many details may still be missing. I can then start to annotate by hand on the printed score as well. That often looks a bit like this:

Gradually these ideas are sifted through and migrate to the printed score. And you’d think that would be the end of it, but sadly it isn’t – the really tricky part is how to make the score as clear as possible for the performer. The whole interface between composers and performers is, like the written score, a very strange thing, an anomaly in world music as a whole, and I am always learning how best to communicate my ideas via the printed score. And as all composers approach the creation of music differently, so performers understand what is on the score in as many different ways. My touchstones are to be consistent, and when in doubt, subtract rather than add something.

Even when the piece has been performed I may touch up and change my mind. Its seldom I consider a piece ‘finished’ – its just the way it is at that particular time, and one might change it some other time. But one day you just stop – there’s just some place deep in one’s mind when you know you’ve done enough and can’t really change it for the better. This doesn’t happen very often.

Then its off to the printers. If you go back to the top of this page you can click on individual works to browse completed scores – and order them if you wish – as well as learning more about the pieces and hearing performances of them.