The Aldeburgh Festival 2023 begins tonight (with a performance of the new opera, Giant, by Sarah Angliss) so the premiere of Quartet Black by the Heath Quartet is now only just over two weeks away…

The colour of the piece: I’ve received a number of questions about the title-word ‘black’ – mainly whether it accounts for something specific or if it does, in fact, just means the colour, black – and then whether black as representative of sadness and sorrow (like in John Donne’s Holy Sonnets) or a comforting, enveloping, magical colour (as is revealed in various chapters of The Owl who was Afraid of the Dark…)

Or a smart, slick modern one like evening dress…

Or any combination of these…

The music doesn’t represent a specific, physical colour – but rather a mental sorrow and sort of, well, horror.

Time, and What to Do: a distinguished composer and close friend is visiting Southwold from out of town. Discussions over coffee turn to ‘what happens’ in a piece music. How does a composer ‘decide’ what is going to ‘happen’ in their piece – and do they indeed decide this at all, or does it come down to the brief, context, instruments, or indeed the initial energy and character of something they have written. And does what one decides in this regard on one day mean the piece cannot be another way on another day.

Readers of my writings here and elsewhere will know I am inherently suspicious of the language of music ‘going’ somewhere, or ‘moving’ from one place to another, or such and such ‘happening’ in a piece. I am not sure I really believe the word ‘happening’ can be used to describe the unfolding of music in time – yet it is frequently described in this way.

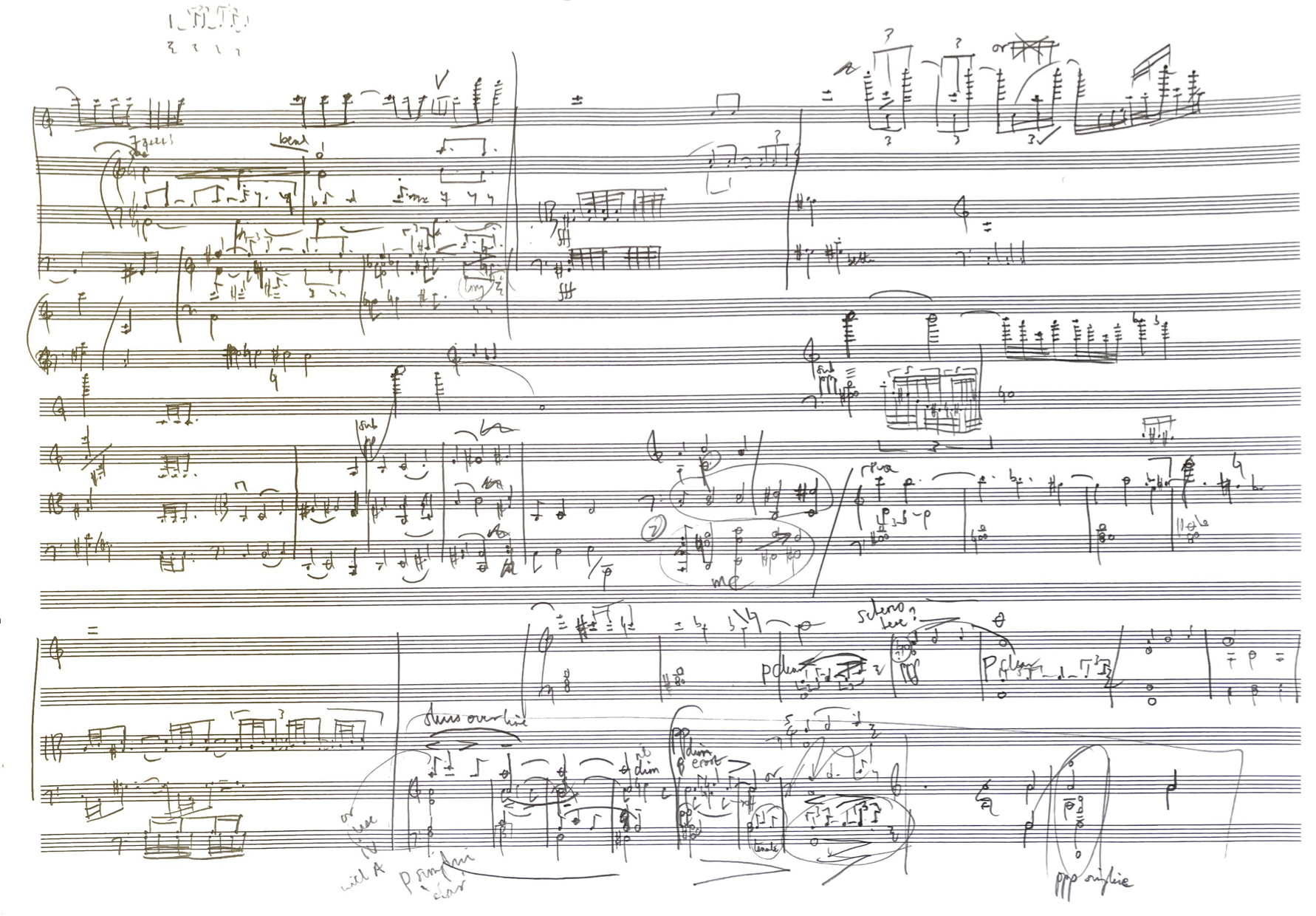

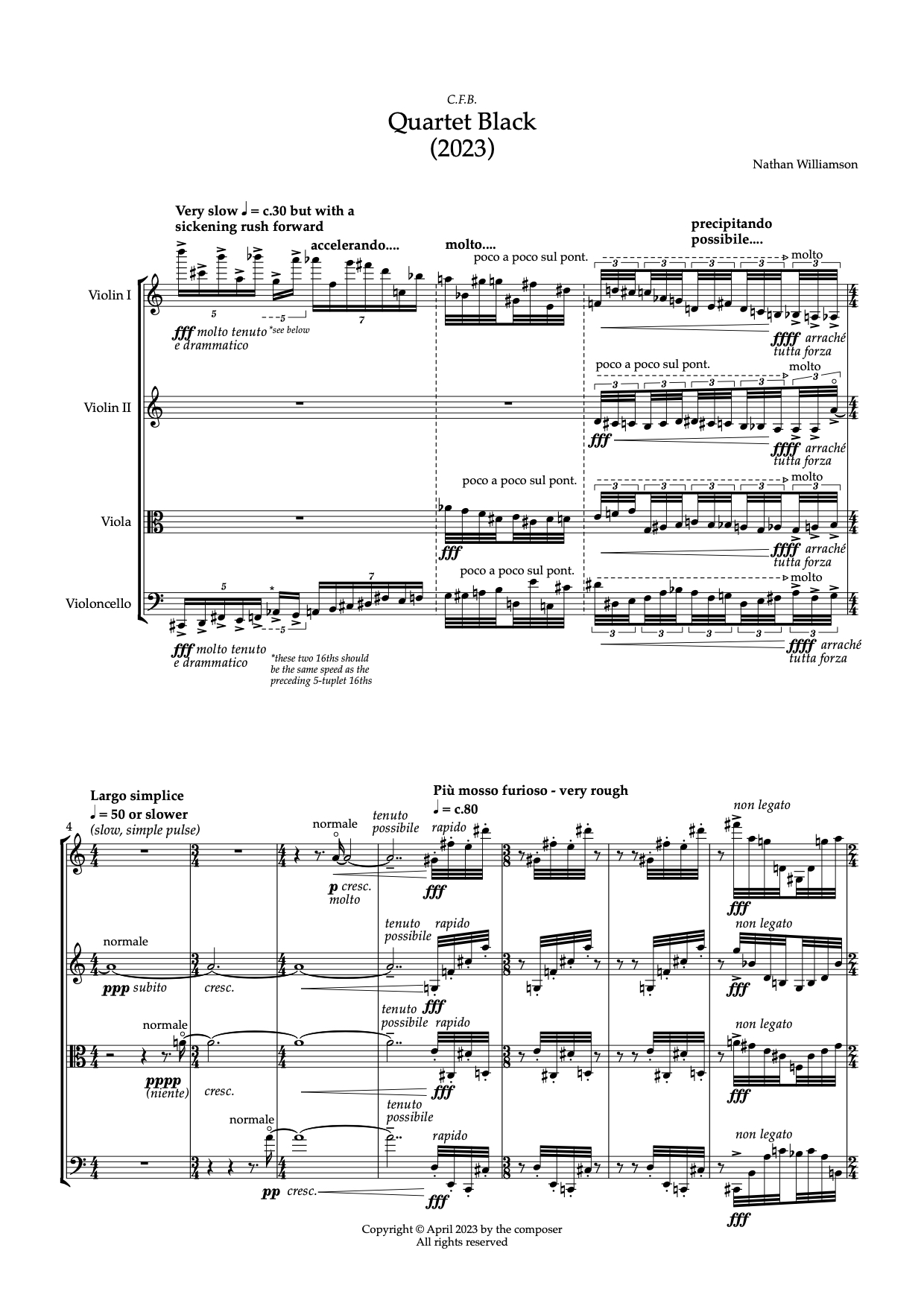

Except to say that, in Quartet Black (and in a massive majority of other pieces, by anyone) notes are arranged in a left to right reading score, ordered to occur in a systematic division of time (known as ‘rhythm’) and the pages are fixed in a certain order. So in that sense one thing happens before/after another.

But this sequence of events/occurrences/sounds are organised by me, the composer, purely by instinct. I do have a certain sensation of what a Quartet should feel like and which musical events, and the order of those musical events, will lead to a sense of a complete piece having been performed. I don’t call this structure – the only structure I care about is the roof over my head. I prefer the word ritual.

Instincts: instincts are often highly prized these days – some sort of ultra-pure thought, or supernatural inspiration which we cannot account for. However my ‘instinct’ tells me that my instincts are more often than not likely to get me into all kinds of trouble.

If a good instinct is treasured for its purity and magical unaccountability, is not a bad instinct something to be taught or trained away – and therefore is not the praise of instinct in general the criticism of established wisdom and learning? We are often encouraged to be ourselves and find out who we really are – and rightly so – but it is not a good idea to assume that such an approach will unleash universally positive forces.

I recall an almost uncontrollable sense of anger and injustice when my teachers (or one teacher in particular) would say ‘be yourself’, and ‘express yourself’, or ‘find some passion’, and then criticise (or worse, mock) me for doing so in the completely ‘wrong’ way. Fortunately I had another teacher who taught me a better way, which is to train one’s instincts – to be aware of them, accept them, and follow them positively and creatively – and, yes, change and mould them over time.

One could say I have used my instincts in writing Quartet Black, in so far that I have no justification as to what I have written other than it is what I wanted to hear. So yes, pure instinct, except to say that my musical instincts are the most worked, refined, trained, exercised and focussed part of my mind.

The Sequence: the events of the piece, arranged instinctively, could be rearranged to create a different sequence. Or could they? What is the difference between me, as the composer, hearing the sequence of the music playing in my ear, and you, the listener, hearing the music in performance? I wonder if the only thing which really fixes a work’s sequence is the fact that it has been heard successfully like that before – but sometimes it might benefit from cutting or re-ordering or changing that sequence for a different context. Musicians used to undertake this sort of adaptation a lot more than we are accustomed to these days – and not just with their own music either…

This is the kind of thing composers think about. Not so much ‘what the notes are’…