Research, arranging, editing – not to mention musical preparations and rehearsals – of Thomas Pitfield’s First Piano Concerto came to a conclusion a few weeks ago with the performance of this largely unknown work in Aldeburgh with the Prometheus Orchestra and conductor Matthew Andrews.

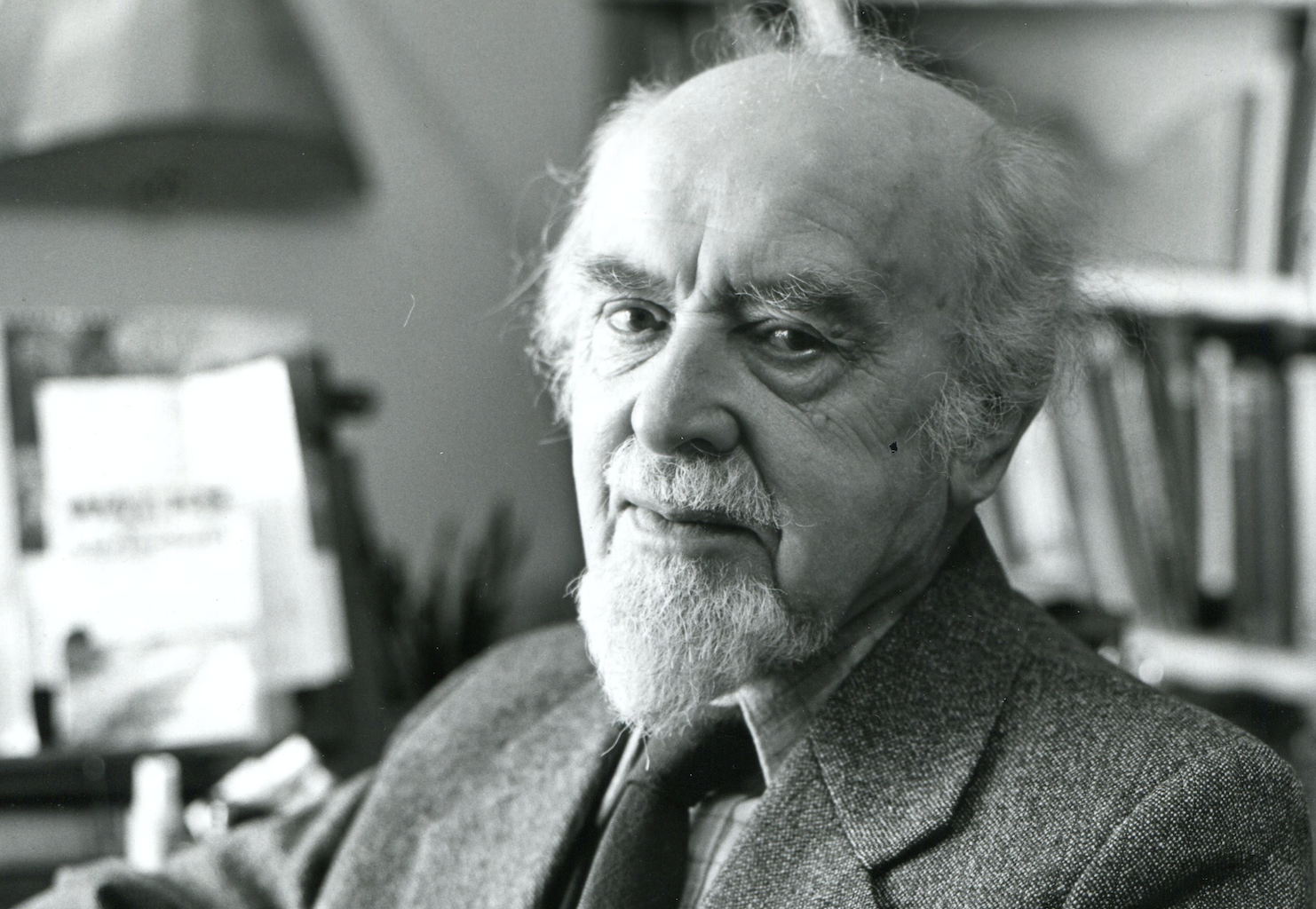

Thomas Pitfield was born in Bolton in 1903 and died in 1999. Alongside his composing career he was a professional artist, illustrator, and teacher of handicrafts. His education was unusual to say the least – removed from school (illegally) aged 14 to be apprenticed to the engineering firm Hick Hargreaves, he painstakingly built up savings to undertake a single year of tuition at the Royal Manchester College of Music, aged 21. This course gained him no paper qualifications, so in a further bid for independence he trained as a teacher of art and cabinet work at the Bolton School of Art.

In his early career he taught these skills at various institutions in Lancashire and the West Midlands, also performing as a freelance cellist, organist and pianist – and composing, a lot. When some of his pieces were accepted for publication by OUP, Pitfield illustrated the covers himself, making such an impression that he was subsequently commissioned covers for many other composers’ works, most famously Benjamin Britten’s Simple Symphony.

The full orchestral score of the First Piano Concerto is dated 1946-7, which was something of a pivotal year in Pitfield’s life. He was invited to join the composition faculty at the Royal Manchester College in 1945, but the offer was withdrawn after what Pitfield later described as ‘backstage machinations’. Did this snub lead to a need to prove himself as a more ’serious’ composer, and so the composition of this ambitious Concerto? It seems likely – in the same year Pitfield submitted 147 works to publishers and fulfilled a commission for 100 piano pieces for use in the Royal Academy of Dancing’s examinations. Such industry may well have succeeded – the College reinstated its offer in 1947. Pitfield served on the faculty until his retirement in 1973, remembered with great affection by many distinguished students, including Ronald Stevenson, John McCabe, John Ogdon and Max Paddison.

The First Piano Concerto is certainly one of Pitfield’s finest achievements. Premiered in 1959 by Stephen Wearing and the BBC Northern (later the BBC Philharmonic) Orchestra, the piece remained high in Pitfield’s estimations: having completed the work the year he joined the College faculty, with uncanny symmetry he made extensive revisions to the score the same year as his retirement.

The work is an excellent example of Pitfield’s exquisite, trademark balance of the personal and heartfelt which somehow manages to not take itself too seriously. Most striking musically is the range of character Pitfield can conjure – one finds oneself casting around for references and bringing images, even storylines, to mind. There runs throughout a lightness of touch which, if not exactly unique to Pitfield, is certainly highly unusual amongst 20th Century composers of major orchestral concert works.

The first movement is of very free structure – it begins like a Sonata Form, with two distinct subjects, but following the apparent ‘development’ and a truncated statement of the opening theme, it simply stops with an abrupt cadence. The second movement combines a slow, funereal chorale and a quirky, rather spooky Scherzo in a Rondo-like exchange of ideas. The brilliant finale is (in Pitfield’s own curious description) a ‘gay and impudent Rondo with a fugal appendage’. He employs a technique found in several other of his larger-scale works of bringing back themes from previous movements at its conclusion – material from the first movement forms the basis of the final fugue, which is in turn combined with the second movement’s Chorale, now played by the full brass section in heroic style. Its a thrilling denouement and a powerful climax, followed by a brilliant virtuosic coda.

Pitfield’s music has long fascinated me, as does the man behind it, and having the opportunity to study and perform this work fulfils a long held ambition, and I am immensely honoured to have been asked to perform the work. I strongly recommend the superb recording on Naxos by Anthony Goldstone, the RNCM Orchestra and conductor Andrew Penny. Also on the disc is the Second Concerto, as well as several solo piano pieces and a Xylophone Sonata, all performed by Peter Donohoe.

Thomas Pitfield Composer, Thomas Pitfield Composer, Thomas Pitfield Composer, Thomas Pitfield Composer, Thomas Pitfield Composer